Woods, trees and spending reviews

It’s been a long time since we’ve had a proper spending review in this country - and by “proper spending review” I mean, something which actually sets the course of government policy for more than a year. These events are often overshadowed by the Budget, which is where taxes are set and everyone learns how much duty they’ll be paying on a pint of beer. But if you’re looking for a document which has longer-term consequences on our lives, the spending review is probably the one to look towards.

Covid, Brexit and political instability have meant that the last couple of spending reviews have largely been one-year keep-things-ticking over jobs and you have to go back all the way to 2015 for the last multi-year affair. But even this wasn’t quite the same thing, for all of George Osborne’s reviews - 2010, 2013 and 2015 - were less about spending than about not spending. They were austerity reviews.

All of which is a somewhat long-winded way of saying that of all the pieces of news emerging from the Treasury this week, my hunch is that in the long-run the spending review might end up being the most consequential. What does Tory government actually mean? How does this government attempt to extract value for money from a public sector which is about to get year-on-year increases in their budgets? These are interesting questions and this week we may get some hints of answers and, in the process, begin to understand a bit more about what kind of economics policy Rishi Sunak’s Treasury is interested in when it is no longer having to firefight Covid and lockdowns.

In the past few weeks I, along with most of the press, have been sprayed with such a gigantic torrent of press releases about the Budget and SR that we are now mostly up to our necks in gush. Most of these releases are just that, and Chris Giles has a good run-through of whether they actually add up in the FT.

I have a broader concern, however, which is that by focusing on all these little bitty bits of news, we lose sight of the big picture. Yes we have plenty of emails about the trees; what about the woods? With that in mind here are a few things you need to know about it, some of which I’ve borrowed from a shorter piece I’ve written for Sky News.

The first is that spending reviews like this actually don’t concern themselves with all the government’s spending, but instead with quite a specific part of it.

Here’s one way of thinking about it. In the most recent year for which we have numbers, which is to say 2020/21, the government spent just north of a trillion pounds. The spending review isn’t about all of that money, but only about just under half of it. For it turns out about £600bn of that, what the government calls “annually managed expenditure”, consists of spending on recurring items it can’t really control on an year-by-year basis: stuff like debt interest, pensions and welfare.

Instead what the spending review is really about is a £500bn or so chunk of its spending referred to as “departmental spending”. That chunk can be broken down further: about £100bn of it is capital spending, on investment, new buildings, roads, railways and so on. The remaining £400bn or so consists of day-to-day spending in departments.

Actually you can break it down yet further. Take that £400bn or so of spending (actually £385bn in the latest year). We know, because the Chancellor has already published his spending “envelope”, that this day-to-day spending will increase to £441bn by the end of the three year spending review (2024/25).

So what we’re really interested in is the amount by which it’s increasing: around £56bn. That’s what this really comes down to: £56bn of day to day spending and £13bn of money to be invested. That’s the spending review.

Except that you can break it down even further, which brings us to the second thing you need to know about it: we already know a fair few of the decisions which will be formalised this week. We know, for instance, that £14bn extra is due to be spent on healthcare (that was announced alongside the NICs increase last month). We know that a certain amount - probably around £6bn - needs to go on schools and international aid, based on existing promises. We know a certain amount is to be spent on net zero.

When all’s said and done, then, the real question mark is who gets what’s left, the final £36bn or so of day-to-day spending. The flurry of press releases in recent days from the Treasury, the behind-the-scenes jousting that’s been happening in Whitehall these past months, the briefing and counter-briefing: it’s all been about this £36bn.

Of course, none of the above tells you whether this £36bn is “big” or not. The short answer to this is that yes, it’s pretty big.

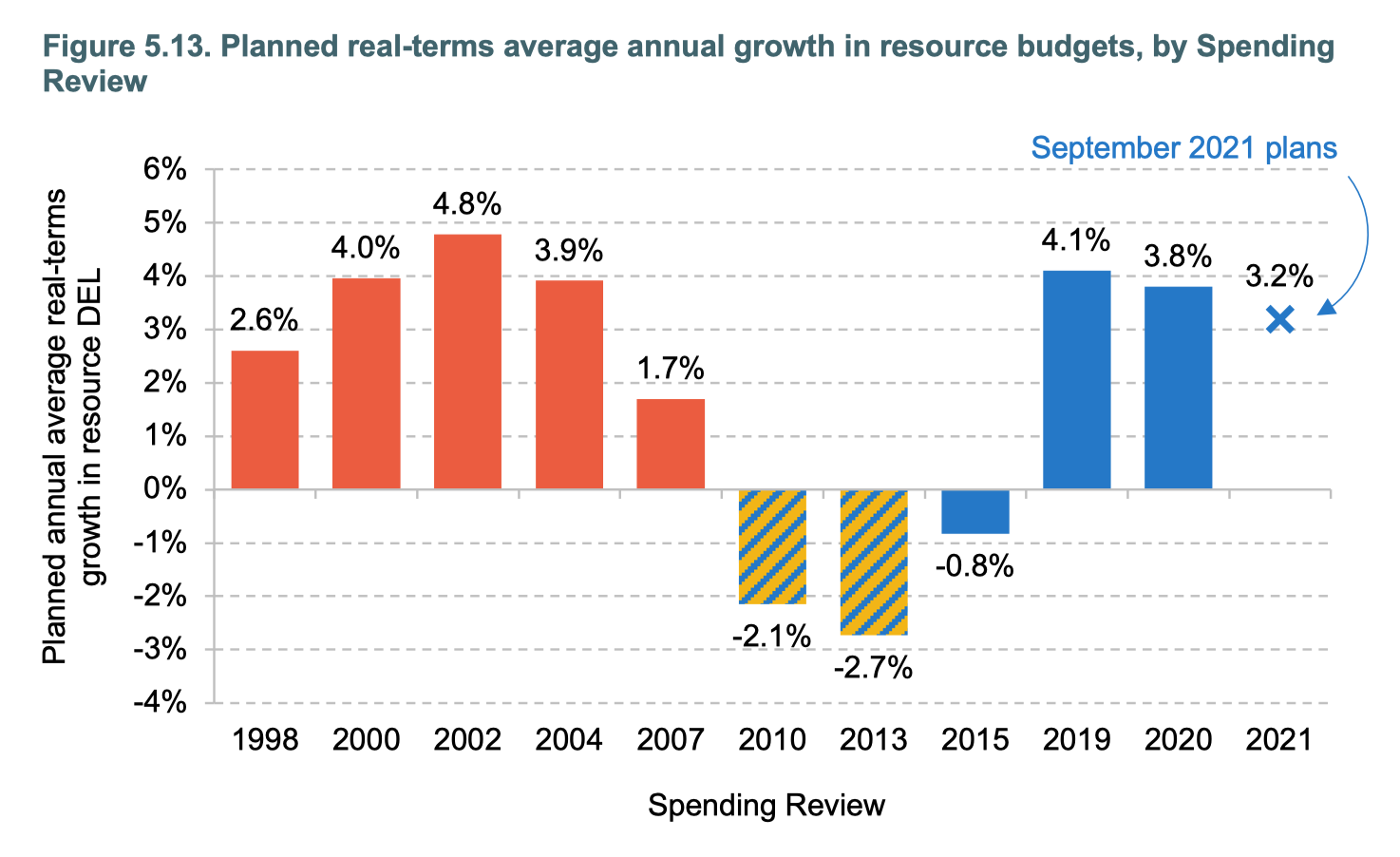

As you can see from this chart from the chart from the latest IFS Green Budget the increases in day-to-day spending will average out at around 3.2% a year, which while not as big as the last couple of one-year reviews, is significantly bigger than Alistair Darling’s 2007 Spending Review and is not far off Gordon Brown’s pretty enormous 2004 review.

Of course, more and more of this increase is getting eaten up by health spending. It used to be said that developed economies had gone from being warfare states to welfare states. Well today, certainly in the UK, we are fast shifting from being a welfare state to a healthcare state.

One of the great challenges of the coming years will be working out how to afford this. You’ve probably already seen charts like this one, also from the Green Budget, but it’s worth trotting out again, since it’s one of the biggest issues we’ll be grappling with in the coming decades.

Healthcare costs aren’t just one challenge facing the public finances; they are by far the biggest challenge, dwarfing even the potentially enormous cost of net zero. At some point this Chancellor - or more likely one of his successors - will have to lay out a plan to afford this. Don’t expect it to be resolved in this week’s spending review.

Comments ()