Rare earths: everything you ever wanted to know

Or rather: everything you never really wanted to know but certainly ought to know, especially since the device you're reading this on almost certainly has rare earths in it

Let’s start with that picture above. The one that looks a little like a satellite image of Mordor. In fact, it might better be thought of as ground zero of the 21st century. Without the mine you’re looking at here you wouldn’t have Airpods. You wouldn’t have electric cars. Or wind turbines. Or most of the modern tech we use on an everyday basis. This is Bayan Obo: the world’s biggest rare earths mine.

Bayan Obo is in Inner Mongolia. China. The first thing you notice if you go anywhere nearby is the pollution, which hangs in the air. For it turns out extracting rare earths from their ores is an incredibly energy-intensive, dirty business. Many mining processes involve waste tailings and lakes of toxic sludge, but especially rare earth processing.

Rare earths are a collection of 17 metals which live in their own special segment of the periodic table. Look at the white elements above. And you can see the rare earths themselves are divided into light and heavy rare earths. Part of the difficulty of refining them - the reason you need to bombard them with all sorts of acids and so on - is that it’s especially difficult to persuade the light and heavy rare earths to be parted from each other. Anyway, these elements are pretty obscure and up until the 1980s were pretty fringe: used in some heat resistant alloys, fluorescent bulbs and a few other things. So they were quite important, but not massively.

That changed in the 1980s with the invention of the neodymium-iron-boron magnet. Now, this technology isn't exactly a household name. But these magnets are incredibly incredibly important. And not just for snazzy Apple headphones (though they're in them too). If it weren’t for rare earths, in fact, you wouldn’t be able to get earbuds that fitted in your ears. Headphones would be a lot more like those enormous ones from the 70s which got very moist on the pads after a few songs…

However, these magnets are perhaps most important today not merely for making small, effective earbuds but for other, bigger applications. Think electric motors and dynamos. When you make them with permanent rare earth magnets they are far more efficient than traditional induction motors (the old school copper-wire ones). Ponder that for a moment and you can start to see why that matters. If your electric car can go much further, that’s a big deal. If your wind turbine can operate so efficiently that it’s still generating decent amounts of electricity in a slight breeze, that’s a big deal.

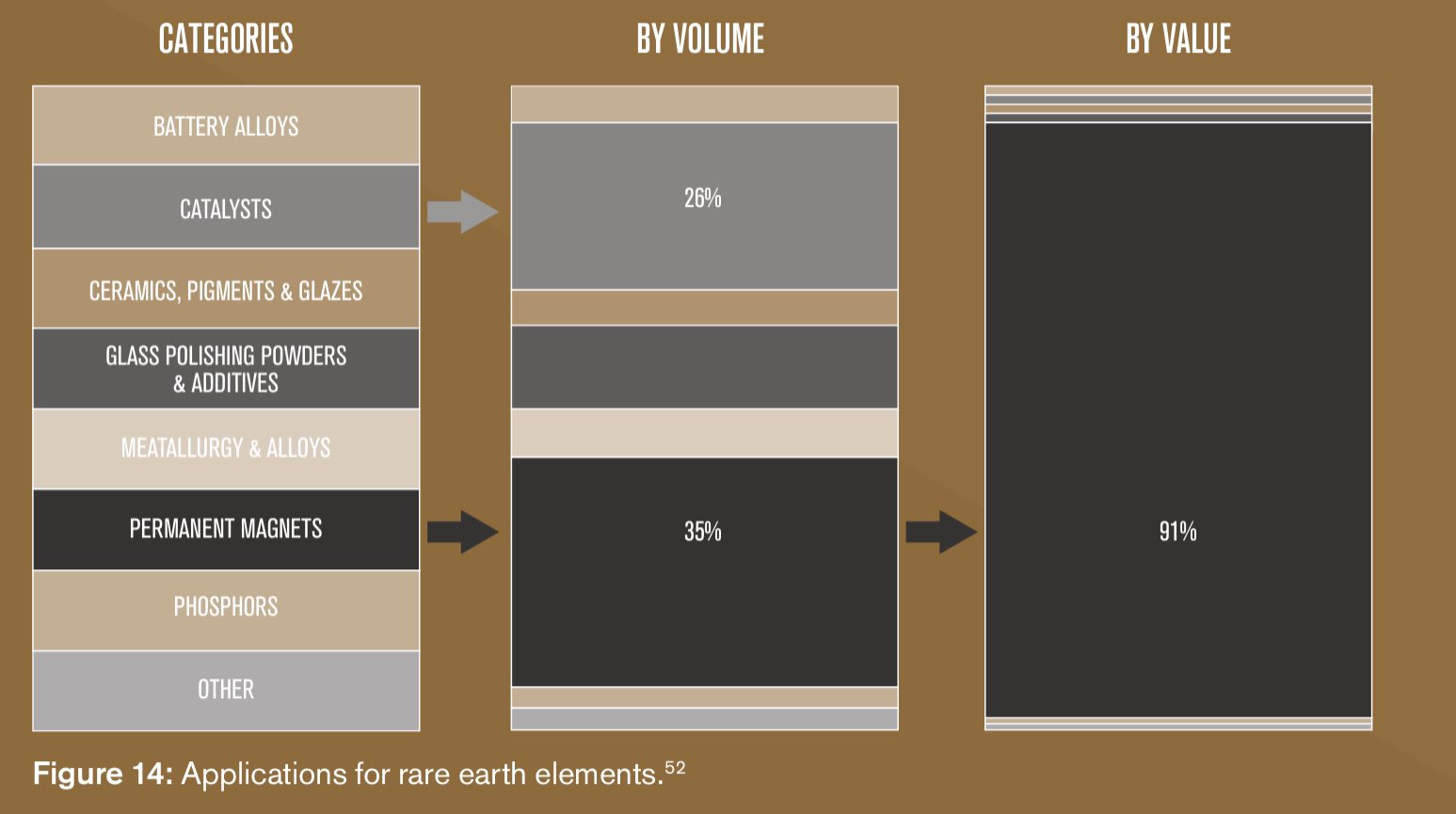

Look at the chart above: the vast, vast majority of uses of rare earth metals is for these kinds of magnets - especially when you look at it in value terms. The upshot is that these days when people talk about rare earths what they are almost certainly referring to is magnets. And here’s the thing. The vast, vast majority of rare earths, and the vast majority of RE magnets, are produced in China. Depending on how you count it, we're talking abt 90%ish. So the chances are the magnets in your smartphone or earbuds or hard disk or electric car came from China. And very possibly from the Bayan Obo mine we began by looking at.

China’s dominance (which you can see in pretty stark terms in this chart) is the result of decades of state support/industrial strategy. For most of the 20th century the US was comfortably the biggest rare earths producer. Surprising as this sounds, the UK was, for a period, quite a big player (in refining, not mining, these materials). But China now dominates. It has most mines; the most processing.

While the US still mines rare earths, the ores actually get shipped to China for processing. And this brings us to an important point, possibly the most important thing you need to know about rare earths. They're actually not all that rare.

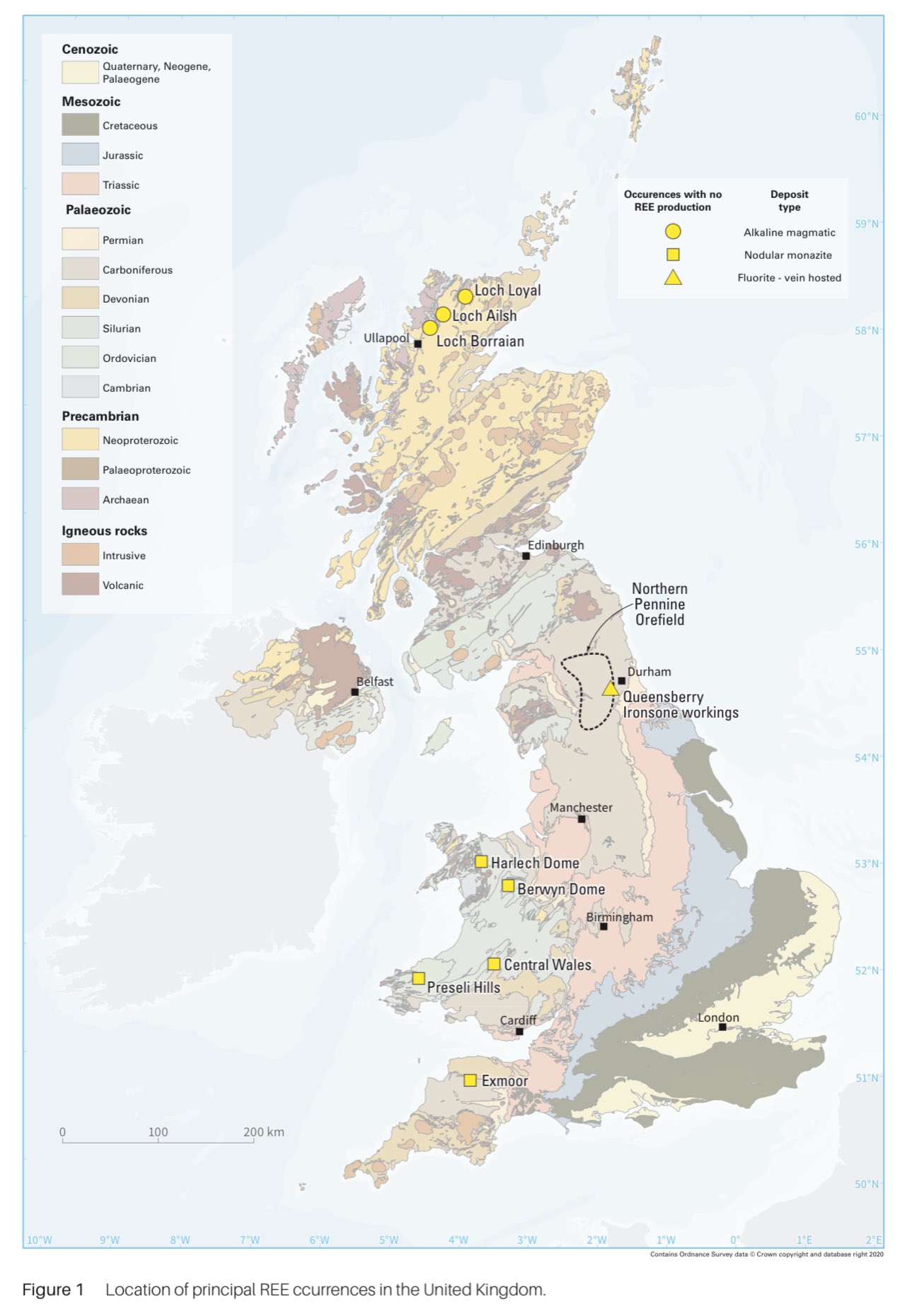

Look: here is a map of rare earth mines around the world. There are quite a lot of them. Indeed, what makes rare earths rare isn't really their distribution. There’s more cerium in the planet’s crust than there is copper or lead. Neodymium is more abundant than tin. There are lots in China. But there are lots elsewhere too. There's even rare earths in Wales & Scotland. Have a look at the map below from the British Geological Survey. Those yellow circles and squares could be promising rare earth mines.

So why do we call rare earths “rare”? It’s not so much about finding them, but about finding a way of getting them into their pure form - in other words processing them. What we call mining isn’t just about extracting the ore; it’s about separating the metal you’re after from other things in that rock. This is no mean feat for many metals. For rare earths it is really, really tough, which has some important implications.

You’ll probably have noticed when people talk about rare earths the implication is often that what we need is to find the right mine with the right materials in it. Look: there are rare earths in Afghanistan! Look there are rare earths in China! Well, helpful as it is to have a decent supply of uniform ores you can chuck into a processor, that misses the main point, which is that there’s plenty of this stuff around (probably even more than we currently appreciate since, unlike with gold or copper we've only started looking for it properly).

What's really needed is a better way of processing the ores. A process that’s more efficient, less pollutive, not so reliant on China and, ideally, one which can work on small batches of rocks rather than doing it at terrifying scale like in Bayan Obo.

Here there's some encouraging news. Work is progressing on this in US, Europe and China. But it's slow work and it's not altogether clear there's enough investment going into it. The UK government talks a lot about gigafactories (where car batteries will be made) but far less about this stuff. Yet it’s a very important part of that supply chain.

And then there's the environmental challenge. If we want electric cars we need rare earths (also battery materials but that's another story for another day). So: do we ship in rare earths from China where they're produced at Bayan Obo (or places with even worse pollution)? Or do we start processing them here? There are a few companies planning to ship rare earths to processing plants in the UK. But they're v early stages. And these plants would almost certainly raise our net carbon footprint. How will that go down among environmental activists?

It brings us to a deeper issue here in the UK (but for that matter in most developed economies too). We've done very well - much better than many expected- at bringing down our domestic carbon emissions (look at the white line above). But in part we've done so by deindustrialising: by shutting down factories and buying in goods from overseas. Our imported emissions are quite chunky - look at the black line above and the gap between the two.

So things like rare earths are an interesting test case in our environmental strategy. But they're also a test case in how serious the west is about the green revolution. Because the dirty truth of net zero is that getting there involves a fair amount of mucky work.

We will still need steel for our structures (even more so for poorer countries as they develop). Copper for our electric cars. Cement for cities. Lithium, cobalt and other metals for batteries. Rare earths for motors and wind turbines and electronics. This helps explain why commodity prices are going through the roof. Everyone wants their own green new deal. This is a massive: perhaps the biggest economic story of the coming decades. Even as we wean ourselves off fossil fuels, the world's appetite for materials to help us create that green promised land is actually increasing.

There are plenty of great resources on rare earths online but of particular note and interest is this report out from Birmingham University’s Centre for Strategic Elements and Critical Materials and the Critical Elements and Materials (CrEAM). In fact, most of the pictures and maps in this blog came from there. I also wrote a Times column on rare earths not all that long ago. And I’ll be posting more stuff on this topic - our reliance on the material world - in the coming months.

Comments ()