No-one played a blinder here

At some point amid the chaos and political drama of Friday afternoon I had a snatched conversation with someone from the world of politics. Liz Truss had just fired Kwasi Kwarteng and admitted, in a slightly excruciating press conference, that her corporation tax freeze would need to be ditched, and all because of the market reaction in recent weeks.

This person’s assessment of the backstory? “Andrew Bailey has played a blinder.”

And it is tempting, superficially at least, to agree. After all, it was no coincidence that it was yesterday that the Chancellor lost his job: that day, Oct 14, was the very day the Bank of England Governor had chosen to end the emergency intervention in gilts markets. He didn’t have to end it then, you know. There was nothing intrinsically special about Oct 14. He could have extended the deadline by days or weeks. But he didn’t. He stood up on a stage in Washington last week and said there were “three days left”.

The governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, tells an event in Washington that funds have 'three days left... to get this done' after a series of interventions following the government's mini-budget.

— Sky News (@SkyNews) October 12, 2022

More here: https://t.co/Jr3owg7b1v pic.twitter.com/CMPBnKUccn

That, goes this version of history, was the moment that sealed the Chancellor’s fate: because at that point, with gilts markets still frantic and the pound wobbling, it was clear that it was up to the Chancellor to do something.

In the event, as we now know, that something was done not by the Chancellor but to the Chancellor. A u-turn was choreographed in Downing Street and leaked to the press. That leak seemed to cause such an enthusiastic response from financial markets that it became very difficult not to go ahead with the u-turn, at which point it became doubly difficult to keep the Chancellor in office. Out he went, and so did Liz Truss’s grand economic plan. Trussonomics is well and truly dead.

You could certainly argue, as some have, that it was the Bank of England Governor, alongside markets, who really caused the ejection of Mr Kwarteng.

Market, plus Bank of England

— James Meadway (@meadwaj) October 14, 2022

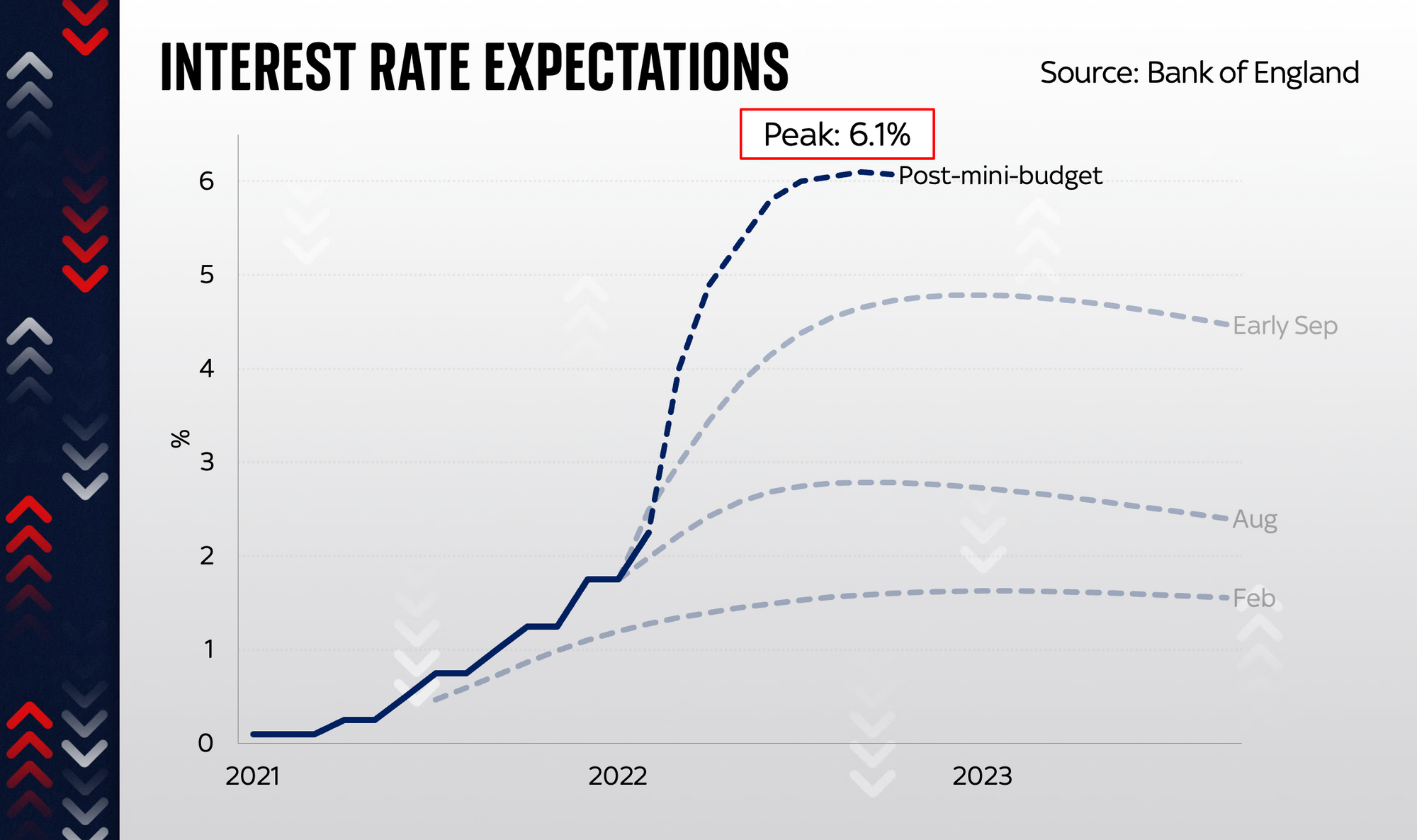

And you can if you choose go even further along this Bank-of-England-played-a-blinder road. Up until this crisis the Bank was heading for a very sticky few years. Interest rates were rising. There were and are legitimate questions about whether the institution was doing a good enough job in fighting inflation. More to the point, everyone could see that borrowing costs were going to have to rise. And that was going to end up being terrifically painful for households. And as often happens when there’s a lot of economic pain, there would inevitably be a lot of economic blame.

The significance of this looming moment hasn’t been much remarked on. To be fair, there’s a lot of other stuff going on right now. But it has long been a very big worry at Threadneedle Street. Don’t get me wrong: the Bank and its Monetary Policy Committee don’t care all that much about popularity - and they’re not supposed to. They’re supposed to keep inflation as close as possible to 2 per cent.

However, more than one senior person has told me, over the past year, that they are intensely aware that as interest rates rise in the coming years, the Bank will likely become very unpopular. It will be introducing a dose of unpleasant medicine it hasn’t ever really had to in such quantities since it became independent in 1997.

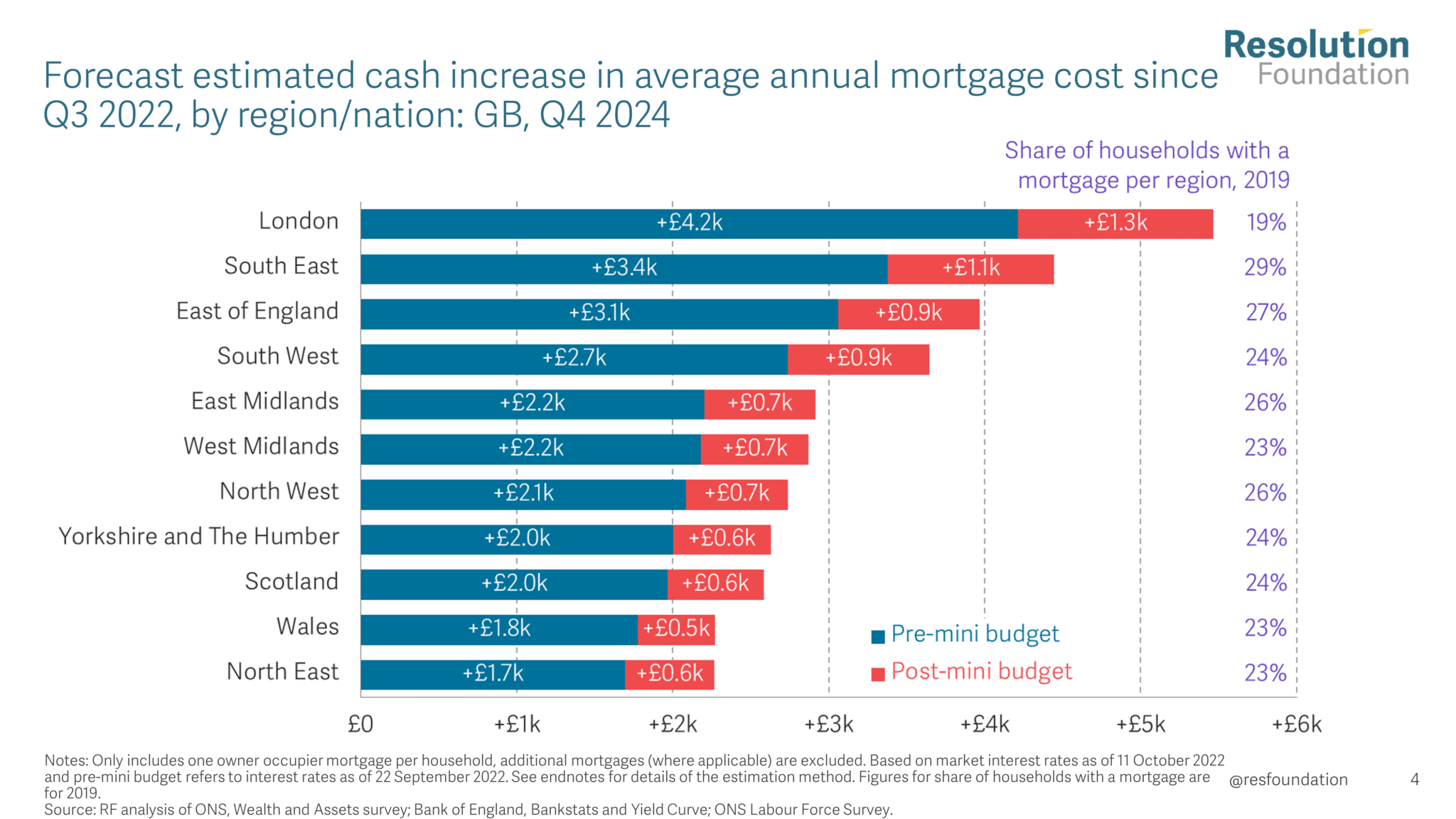

Yet here’s the remarkable thing about the past few weeks. Somehow, because of the abysmal reception for the mini-budget, because it pushed up interest rates across the economy up very sharply indeed and because there was an instant impact for some consumers (mortgages are now considerably more expensive than they were a few weeks ago - above 6 per cent for two years rather than above 4 per cent), somehow most of that mortgage blame seems to have attached itself to the government.

And you can see why. The “credibility premium” lenders have added to Britain’s interest rates was suddenly added in the days after the mini-budget. There was a direct impact on interest rates.

However, when you look at the entire impact of higher interest rates on families, as the Resolution Foundation has, actually “only” about a fifth of the increase in rates could plausibly be laid at the Government’s door.

Now it’s possible the Conservative party shakes off this association. But it seems equally plausible that the party gets tainted by this episode and blamed for the tangible impact - the thousands of pounds of impact - that homeowners end up feeling for years ahead. In political terms, it is hard to underplay how toxic this could end up being.

It's tempting to compare it with 1992, the year the UK was forced out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, since that was another moment where the party was dealt a lasting blow to its credibility. But there are two reasons to believe this is potentially worse. First, in 1992, Britain's crisis was not unique. Many other European nations were facing precisely the same issue at the same time. Italy left the ERM in September 1992. Britain's shame was diluted. Just as, if not more importantly, the end of ERM membership was the beginning of a massive economic release for the country; the pound fell and unleashed a potent recovery in exports and activity. Never say never, but that seems a lot less likely this time.

Anyway, from the Conservative party's perspective, 1992 was an utter disaster, leaving its popularity in shreds. This feels uncannily similar. And even as the politicians get lambasted for the crisis, the Bank of England seems to be doing well, surprisingly well.

So you can see why so many people think Andrew Bailey “played a blinder”, why he is being lauded as the “central banker of the moment”. The Bank has ended the past few weeks with significantly more credibility and more institutional strength than it previously enjoyed - and all in a period of deep economic insecurity.

Introduced as “central banker of the moment” at IMF event, Bank of England Gov chose moment to suggest interest rate rise could be higher than expected next month. “Best guess is inflationary pressures will require a stronger response than we perhaps thought in August." @SkyNews pic.twitter.com/deRxrAeJ1g

— James Matthews (@jamesmatthewsky) October 15, 2022

Yet I’m not so sure this was anything like the “masterplan” some have interpreted it as. And this comes back to something quite important - something which will be obvious to anyone who spends much time talking to central bankers but not necessarily to those outside the bubble.

There were two critical reasons the Bank imposed such a strict deadline on 14 October, neither of which had much to do with Mr Kwarteng. The first was that the Bank’s Financial Policy Committee was worried that without some strict words, the fund managers attempting to extricate themselves from their problems might have gotten too used to the intravenous drip of central bank support. If the deadline kept slipping, what was to keep them from exiting or changing their LDI strategies and beginning to fix the system?

Second, and even more importantly, there is big contradiction at play within the Bank itself. Up until this intervention, the Bank’s monetary policy committee had been poised to begin selling off some of the enormous mountain of govt bonds it owns. The intervention, voted for by the Financial Policy Committee - a separate Bank body looking not at the state of the economy but the financial plumbing - involved buying bonds. Clearly you can’t buy and sell something at the very same time, so the MPC has temporarily put off its bond sales (“quantitative tightening”). But it underlines an awkward question: who takes precedence: the FPC or MPC?

The reason for the deadline wasn’t really to put a rocket up the Chancellor’s backside. It was primarily because that other bit of the Bank - the MPC - is about to begin its long period of forecasts and deliberations ahead of its next interest rate decision, due in early November. The deadline was in large part there in order to avoid a clash between FPC and MPC policy - so that we didn’t find ourselves in the perverse position where one wing of the Bank was screaming buy even as the other wing was screaming sell.

This internal contradiction, by the way, is a big deal. And it’s a big deal we’ll probably hear more about soon. The MPC’s official position is still to begin selling off those bonds soon. But I wonder whether that can stand, given how unstable the bond markets are right now. There is an opt-out which says QT cannot go ahead if the market is unstable; my hunch is they activate that opt-out and instead carry on raising interest rates.

But anyway, back to my main point: no-one really played a blinder here. The Bank has come out of the past few weeks in a surprisingly strong position - but I ascribe that less to strategic wisdom than the fact that the government simply screwed things up so badly. Anyway, this crisis is still young. And given the scary noises still emerging from bond markets (noises that have much more to do with the global economy than our own parochial problems) there are plenty of bumps in the road that lies ahead of the Bank. Believe me.

Still. This was a story of cock-ups, plain and simple. The mini-budget was a completely and utterly avoidable mistake. A tragedy. A tragedy for the economy, for mortgage payers and for the Tory party. And the tragic irony is that some of their actually quite interesting ideas about supply side reform are almost certainly gone for a generation.

It was a tragic mistake which coincided with bad luck: in any other time, with global markets less strained, it's possible international investors would have looked upon its measures slightly more kindly and more patiently; they might have given the government more time to come up with credible plans to fund the giveaways. But even so: it was a mistake - a mistake Liz Truss has now sort-of acknowledged, by sacking her Chancellor, appointing Jeremy Hunt and ditching most of the mini-budget.

The Conservative party will likely be tainted by the association with mortgage misery for a generation. Their reputation for economic credibility lies in tatters. And all for a set of measures which could simply have been introduced a little later, once the new PM and Chancellor had pocketed a bit of credibility. No one played a blinder. This was just a mess. An entirely self-inflicted mess.

Comments ()